There are a lot of phrases lawyers use that mean something very specific to them. We sometimes call these terms of art. Some of them are in Latin, like res judicata or nunc pro tunc, while others appear to mean something by the plain reading of the English words, yet actually signify something else entirely. One of these is the term legal fiction.

There are a lot of phrases lawyers use that mean something very specific to them. We sometimes call these terms of art. Some of them are in Latin, like res judicata or nunc pro tunc, while others appear to mean something by the plain reading of the English words, yet actually signify something else entirely. One of these is the term legal fiction.

In lawyer speak, legal fiction means a construct that achieves a certain aim under the law, but is only loosely based in a set of facts, and occasionally divorced from them completely. An example would be something that comes up a lot in criminal litigation: plea bargains. In Ohio, where I practice, there is a general attempt statute. In most cases attempting to commit a crime is still a crime, but since it’s usually less serious to try and fail (in terms of the ultimate harm done) attempt offenses are always one degree lower than whatever the underlying offense would have been.

So when you have a low level felony case, like drug possession, and the prosecutor wants to give a guy a break (something the defense attorney is always looking for too) the lawyers might agree to call the charge “attempted possession” for plea purposes. That reduces the offense one degree, which takes it from a felony to a misdemeanor–a significant distinction for a number of reasons. In many cases, the notion that a defendant caught with drugs only attempted to possess them is nonsense, and totally counter-factual, but amending the charges down to that provides a convenient avenue to resolve the case.

Hence, a legal fiction.

In real life though, there is plenty of actual legal fiction, as in books, movies and TV about the legal process. I write some of that myself. What I’m going to do here over the weeks and months to come is to put a spotlight on some of these, discussing what legal fiction writers get right, what they get wrong and everything in between. In honor of the Supreme Court practice of beginning their term on the “First Monday” in October, I’ll be posting a new entry each month on the … yes, the first Monday.

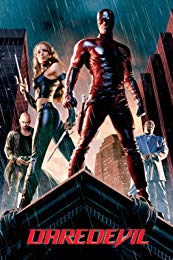

So without further adieu, for my first attempt at this … let’s look at the 2003 Ben Affleck Daredevil film.

While not strictly a legal thriller, the Daredevil character always touches on the law, since his secret identity Matt Murdock is a defense attorney in his normal life.

At least, I think that’s what he’s supposed to be. You’d never know it from watching the 2003 version of the character, which flunks every possible test for courtroom accuracy. It’s not even a close call. This film’s representation of a trial is so bad that I don’t know whether to laugh out loud or throw something at the screen.

The writers had either never been near a courtroom, or just didn’t gave a rat’s ass about approaching authenticity–because this movie’s version of it is pure fantasy.

A few of the points — for one, Murdock proclaims that he only represents innocent clients. Boy, that sounds so … altruistic, doesn’t it? Who could be more dedicated to justice and truth than a lawyer who only handled innocent clients? Who could object to that?

How about every single competent defense attorney ever. Because this is the biggest pile of steaming horse$%#t imaginable.

Defense attorneys check the power of the government to take away the most precious commodity that exists: a person’s life — which the state can compromise by locking someone up, or in some cases, killing them. The one thing no one can make more of is time. Your life is limited. And that is the thing that defense lawyers protect.

You quickly learn in this job that most of your clients are guilty of something, but in our system that doesn’t strip them of their rights. Defense lawyers guarantee everyone has a fair hearing, no matter what they did. That’s the virtue in this line of work, not in ignoring the rights of 99% of people to focus on the wrongfully accused.

Also, good luck making money if that’s your business model. How would that even work? Most clients tell you they’re innocent, at least up front. Would he take their money, only to discover three months into the case that they were — shocker of shockers — lying? Then what? Give the retainer back and, oh by the way, hope the judge lets you off the case that you’ve committed to — after presumably figuring out a way to explain that you need to withdraw without telling the court that it’s because you’ve learned your client is guilty? The absolute last thing you can do ethically is to make your client’s standing in front of the court worse than you found him.

None of this ever happens in real life. Not. Even. Close.

Second, it’s impossible to tell from the courtroom scene in this movie what the hell kind of cases Murdock actually handles. From the way the proceedings flow, you’d think he wasn’t even a defense attorney at all. Clearly, it’s supposed to be a rape case, which would mean he’d be representing the defendant—but no—apparently he’s representing the victim? That makes no sense at all.

Quick legal lesson here: Rape is a crime, which means the State prosecutes someone accused of it, and in that case the victim (Murdock’s client??) doesn’t have a lawyer, because they aren’t a litigant. It’s the State vs. Mr. Accused Rapist.

Disputes between two private parties on the other hand are called civil cases, or what lawyers call torts–the typical forum for any other lawsuit. So maybe he’s a plaintiff’s attorney suing someone for …. what …. assault, maybe? Because crimes like rape are never handled in civil court. You can sue someone for doing harm to you, but only in a specific tort-based way. You can’t sue someone for a crime.

The reason is, if you’re guilty of a crime, you go to prison (or suffer some state-imposed penalty like probation). If you’re liable for a tort, you generally owe money. That’s how the civil system works. If you hurt me, there’s no way to un-hurt me, so the only remedy I have is to get you to pay me to make up for it.

It doesn’t end there though. Aside from apparently having literally zero understanding of even the most fundamental facts about how court works, Murdock quickly proves that no matter what kind of case he’s involved with, he’s an astoundingly bad trial lawyer. He literally asks the apparent rapist to “please state the sequence of events that took place that night” — which is pretty much the worst example of cross examination in the entire history of cross examination.

“Excuse me, Mr. Bad Guy, would you please be so kind as to confess to everything you did wrong here? I mean we went through the trouble of sitting here in a courtroom, and I put on a tie and everything, so if you wouldn’t mind….”

Even if you allow for the notion that with his Daredevil super-senses, he can somehow detect dishonesty in a witness, it’s still laughably bad. Besides, even if he had the power to tell from listening to the guy’s heartbeat that he was lying, what good would that do? He can’t just tell the jury “hey folks, I have super hearing and I can assure you this guy is committing perjury” — plus he already thinks this guy is a rapist, he doesn’t need to be convinced from hearing his vital signs like a human lie detector.

Bottom line: the way an actual lawyer exposes liars in court is by skillful, careful cross examination. You don’t need superpowers, you just need to know how to ask questions properly in a courtroom.

Finally, once they lose the case, on the steps outside the courthouse and flanked by his loyal partner (the indefatigable Jon Favreau–who has maybe redeemed himself lately by bringing us the gloriousness that is the Mandalorian) , he comments that it’s an example of “one more rapist back on the street.” Again, this makes no sense at all.

It’s just been made clear that this can’t be a criminal case, because he’s representing the victim, right??? So if it’s a civil case, which is never about anything but money, then there is no criminal penalty at stake. The guy would be “back out on the street” no matter what had happened, win or lose.

This movie is so mind-numbing stupid in its handling of pretty much everything associated with the legal profession that on literally every possible point, I give it big fat F.